[UPDATE October 2014: Following changes to the BNB platform and supported APIs, this tutorial no longer works as described below. An updated version of this exercise is now available at http://www.meanboyfriend.com/overdue_ideas/2014/10/using-an-api-hands-on-exercise/]

On Wednesday this week (6th Feb 2013) I spent a day at the British Library in London talking to curators about data and the web. The workshop was a full day and we covered a lot of ground – from HTML to simple mashups to Linked Data. One of the things I wanted to do during the day was to get people to use an API – to understand what challenges this presented, what sort of questions you might have as a developer using that API, what sort of things you should think about when creating an API, and hopefully to start to get a feel for what opportunities are created by providing an API to resources.

Since we had a busy day, I only had an hour to get people working with an API for the first time, so I wanted to do something:

- Simple

- Relevant to the audience (Curators at the British Library)

- Requiring no local installation of software

- Requiring no existing knowledge of programming etc.

- That produced a tangible outcome in an hour

The result was the two exercises below. We got through exercise 1 in the hour (some people may have gone further but as far as I know everyone completed exercise 1) and so I don’t know how well exercise 2 works – but I’d be very interested in feedback if anyone gives it a go. The exercises use the British National Bibliography as the data source:

Exercise 1: Using an API for the first time

Introduction

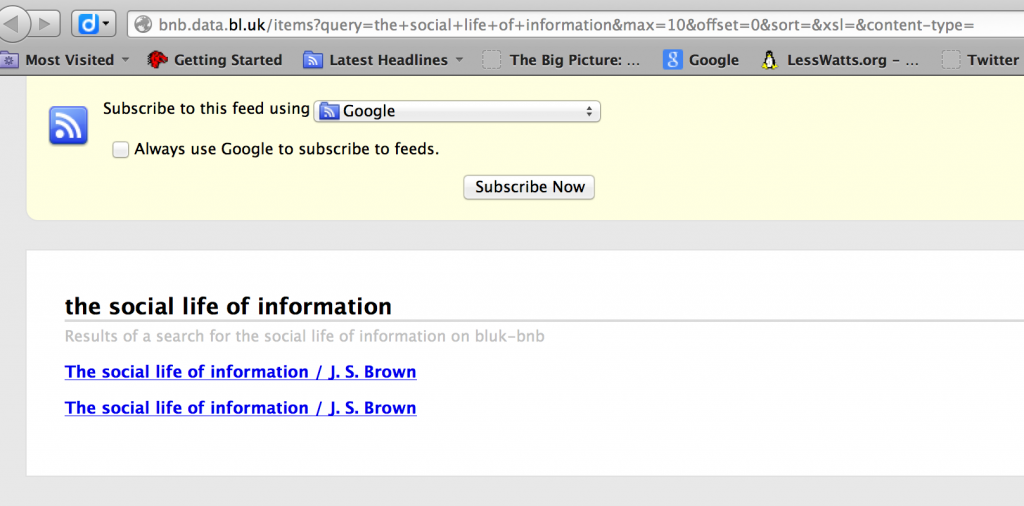

In this exercise you are going to use a Google Spreadsheet to retrieve records from an API to BNB, and display the results.

The API you are going to use simply allows you to submit some search terms and get a list of results in a format called RSS. You are going to use a Spreadsheet to submit a search to the API, and display the results.

Understanding the API

The API you are going to use is an interface to the BNB. Before you can start working with the API, you need to understand how it works. To do this, first go to:

http://bnb.data.bl.uk/search

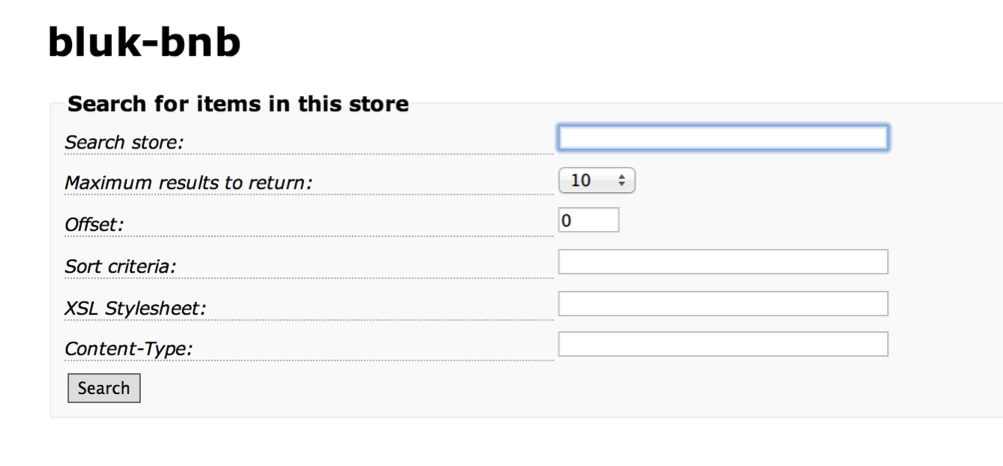

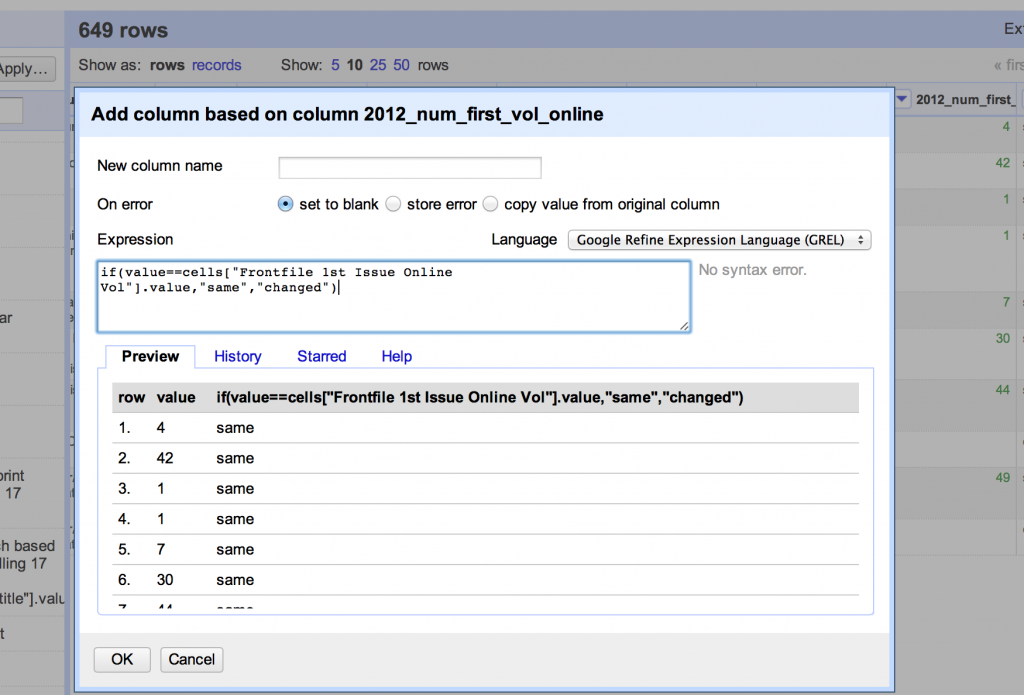

You will see a search form:

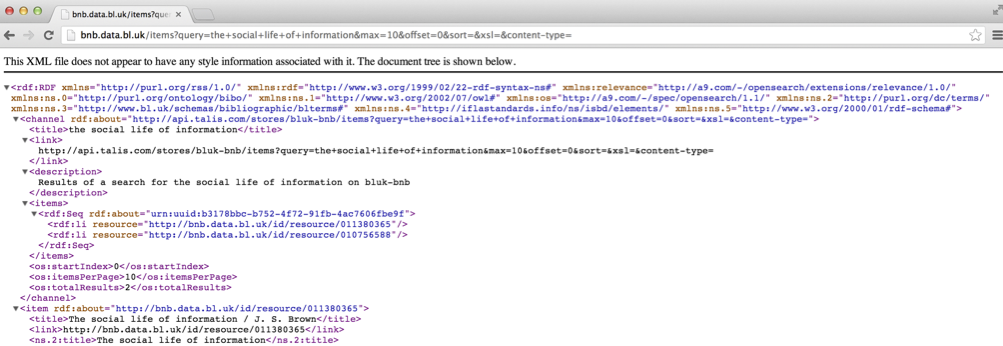

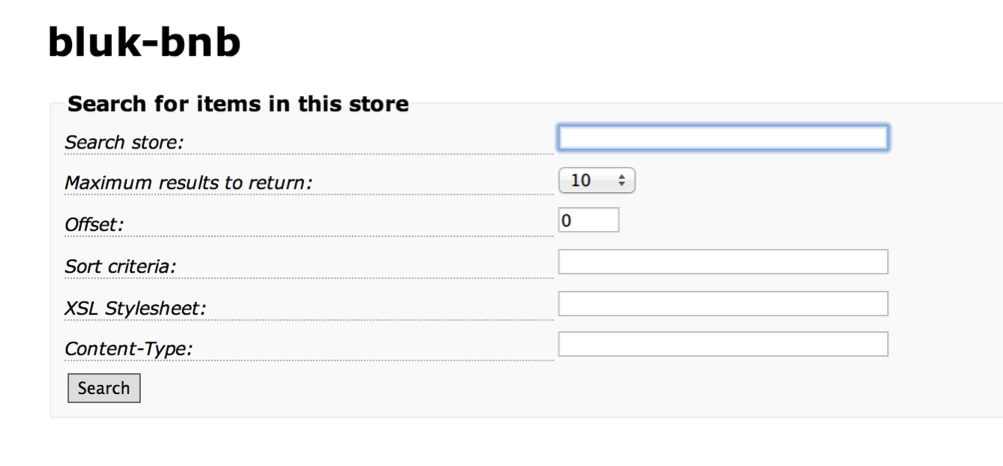

Enter a search term in the first box (‘Search store:’) and press ‘Search’. What you see next will depend on your browser. If you are using Google Chrome you will probably see something like this:

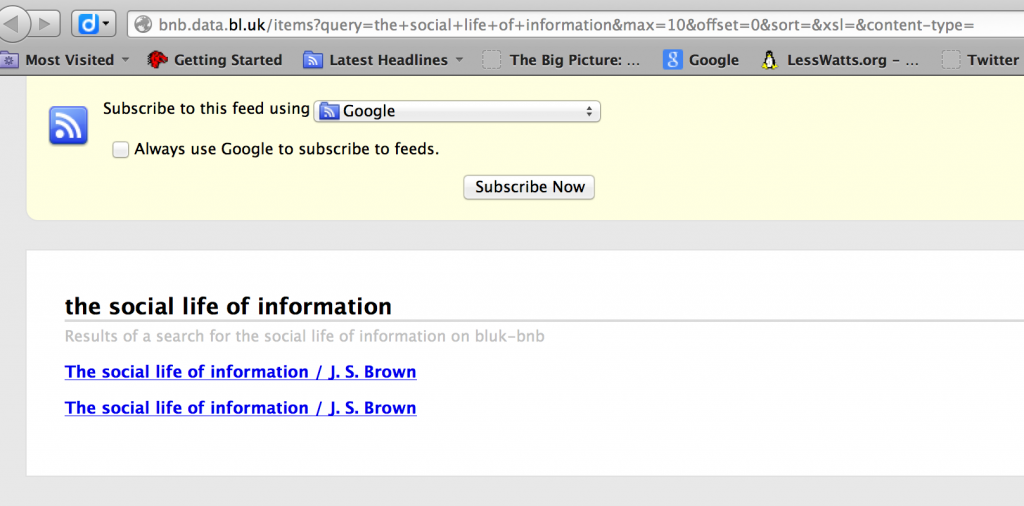

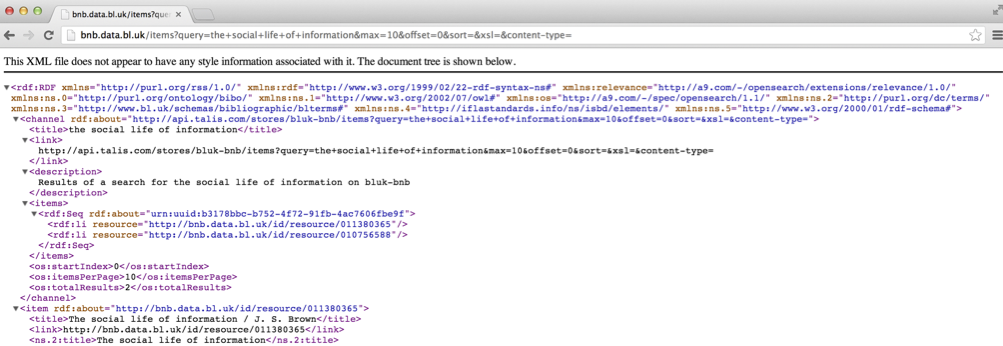

If you are using Internet Explorer or Firefox you will see something more like:

At the moment this doesn’t matter, we are interested in the URL, not the display right now.

Look carefully at the URL – see how the search terms you typed in are included in the URL. The example I used is:

http://bnb.data.bl.uk/items?query=the+social+life+of+information&max=10&offset=0&sort=&xsl=&content-type=

The first part of the URL is the address of the API. Everything after the ‘?’ are ‘parameters’ which form the input to the API. There are six parameters listed and each one consists of the parameter name, followed by an ‘=’ sign, then a value.

The URL and parameters breakdown like this:

| URL Part |

Explanation |

| http://bnb.data.bl.uk/items |

The address of the API |

| query=the+social+life+of+information |

The ‘query’ parameter – contains the search terms submitted |

| max=10 |

The ‘max’ parameter is set to ’10’. This means the API will return a maximum of 10 records. You can experiment changing this to get more/less results at one time |

| offset=0 |

The ‘offset’ parameter tells the API which the first record you want to be included in the results. It is set to ‘0’ meaning that the API will start with the very first record. |

| sort=&xsl=&content-type= |

Other parameters – you can see that these reflect the other parts of the form at http://bnb.data.bl.uk/searchThe parameters are:

None of these are set and are not going to be used in this exercise. |

The output of the API is displayed in the browser – this is an RSS feed – it would plug into any standard RSS reader like Google Reader (http://reader.google.com). The BBC have a brief explanation of what an RSS feed is (follow the link). It is also valid XML. The reasons browsers display it differently (as noted above) is that some browsers recognise it as an RSS feed, and try to display it nicely, while others don’t.

If you are using a browser that displays the ‘nice’ version, you can right-click on the page and use the ‘View Source’ option to see the XML that is underneath this.

While the XML is not the nicest thing to look at, it should be possible to find lines that look something like:

<item rdf:about="http://bnb.data.bl.uk/id/resource/011380365">

<title>The social life of information / J. S. Brown</title>

<link>http://bnb.data.bl.uk/id/resource/011380365</link>

Each result the API returns is called an ‘item’. Each ‘item’ at minimum will have a ‘title’ and a ‘link’. In this case the link is to more information about the item.

The key things you need to know to work with this API are:

- The address of the API

- The parameters that the API accepts as input

- The format the API provides as output

Now you’ve got this information, you are ready to start using the API.

Using the API

To use the API, you are going to use a Google Spreadsheet. Go to http://drive.google.com and login to your Google account. Create a Google Spreadsheet

The first thing to do is build the API call (the query you are going to submit to the API).

First some labels:

- In cell A1 enter the text ‘API Address’

- In cell A2 enter the text ‘Search terms’

- In cell A3 enter the text ‘Maximum results’

- In cell A4 enter the text ‘Offset’

- In cell A5 enter ‘Search URL’

- In cell A6 enter ‘Results’

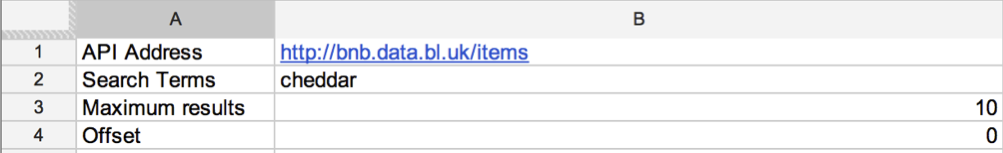

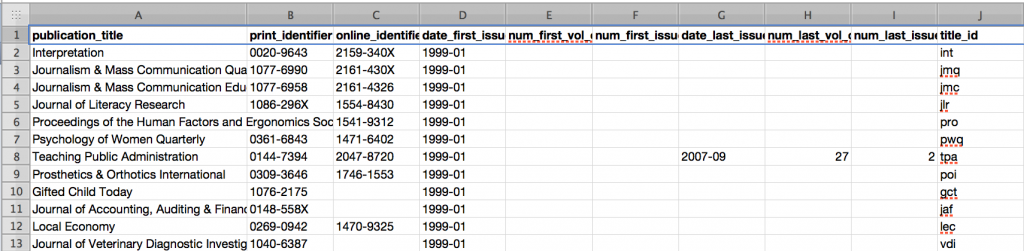

Now, based on the information we were able to obtain by understanding the API we can fill values into column B as follows:

- In cell B1 enter the address of the API (see the table above if you’ve forgotten what this is)

- In cell B2 enter a simple, one word search

- In cell B3 enter the maximum number of results you want to get (10 is a good starting point)

- In cell B4 enter ‘0’ (zero) to display from the first results onwards

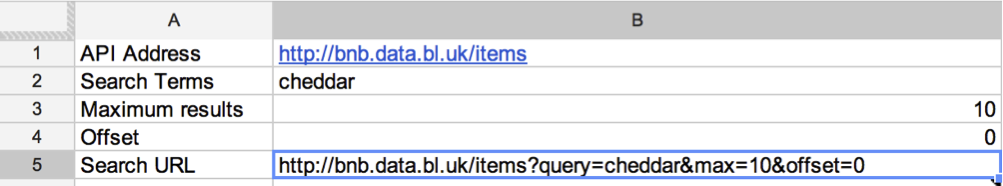

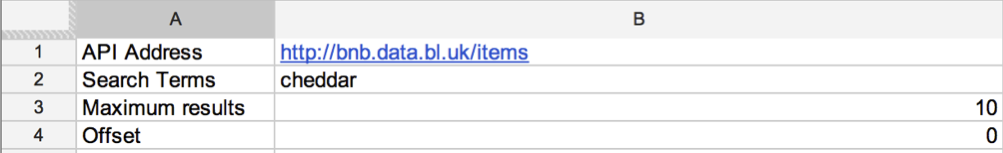

The first four rows of the spreadsheet should look something like (with your own keyword in B2):

You now have all the parameters we need to build the API call. To do this you want to create a URL very similar to the one you saw when you explored the API above. You can do this using a handy spreadsheet function/formula called ‘Concatenate’ which allows you to combine the contents of a number of spreadsheet cells with other text.

In Cell B5 type the following formula:

=concatenate(B1,"?query=",B2,"&max=",B3,"&offset=",B4)

This joins the contents of cells B1, B2, B3 and B4 with the text included in inverted commas in formula. N.B. Depending on the locale settings in Google Docs, it is sometimes necessary to use semicolons in place of the commas in the formula above.

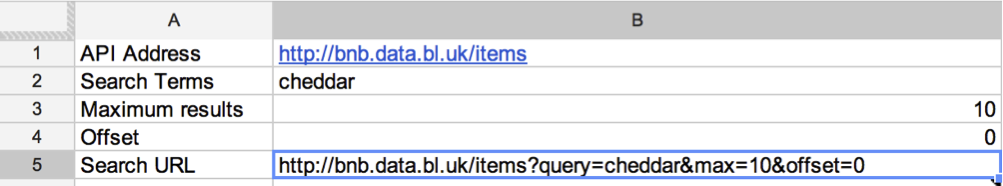

Once you have entered this formula and pressed enter your spreadsheet should look something like:

The final step is to send this query, and retrieve and display the results. This is where the fact that the API returns results as an RSS feed comes in extremely useful. Google Spreadsheets has a special function for retrieving and displaying RSS feeds.

To use this, in Cell B6 type the following formula:

=importFeed(B5)

Because Google Spreadsheets knows what an RSS feed is, and understands it will contain one or more ‘items’ with a ‘title’ and a ‘link’ it will do the rest for us. Hit enter, and see the results.

Congratulations! You have built an API query, and displayed the results.

You have:

- Explored an API for the BNB

- Seen how you can ‘call’ the API by adding some parameters to a URL

- Understood how the API returns results in RSS format

- Used this knowledge to build a Google Spreadsheet which searches BNB and displays the results

Exercise 2: More API – the full record

Introduction

In Exercise 1, you explored a search API for the BNB, and displayed the results. However, this minimal information (a result title and a URL) may not tell you a lot about the resource. In this exercise you will see how to retrieve a ‘full record’ and display some of that information.

Exploring the full record data

The ‘full record’ display is at the end of the URLs retrieved from the BNB in Exercise 1 above. Click on one of these URLs (or copy/paste into your browser). If possible pick a URL that looks like it is a bibliographic record describing a book, rather than a subject heading or name authority.

An example URL is http://bnb.data.bl.uk/id/resource/010712074

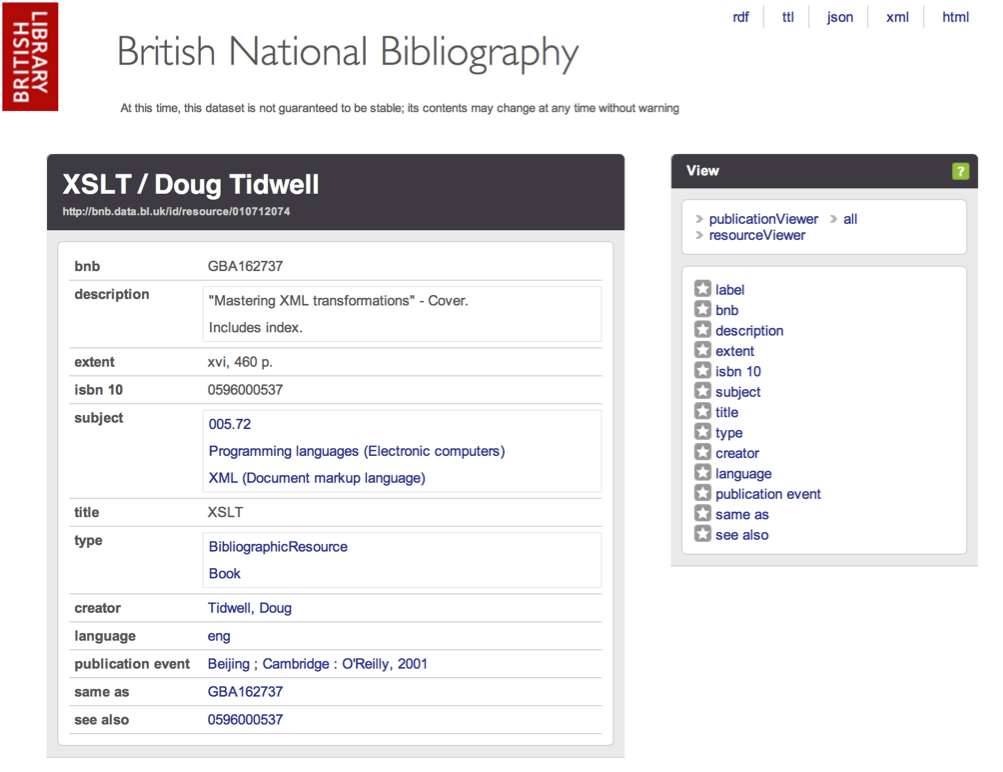

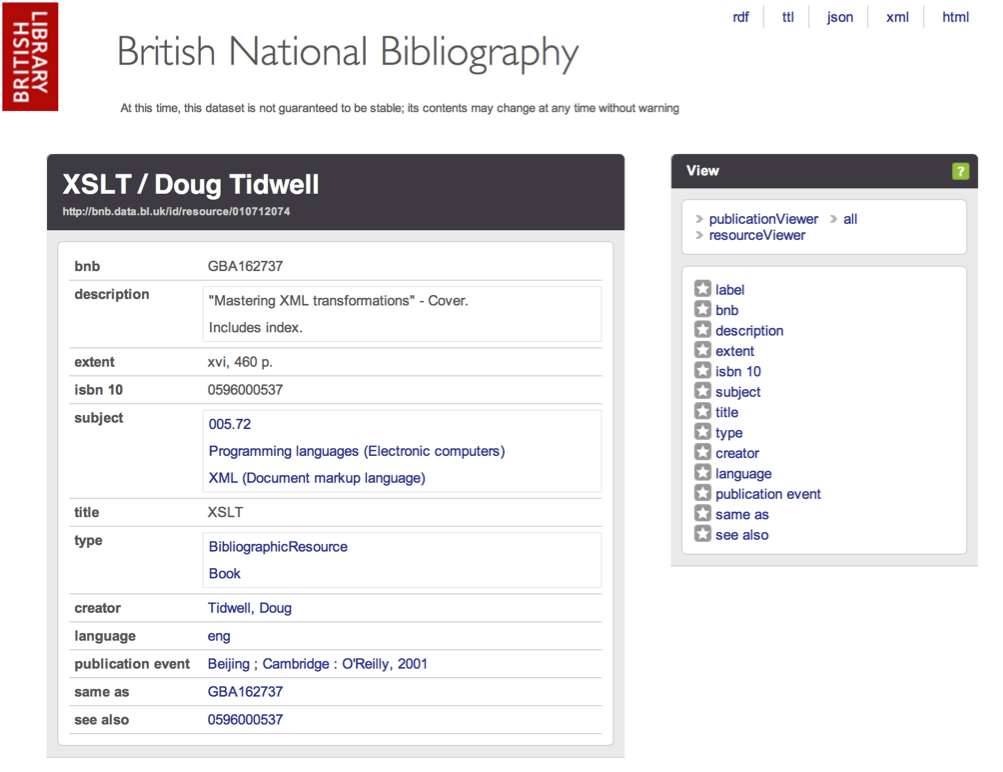

Following this URL will show a page similar to this:

This screen displays the information about this item which is available via the BNB API as an HTML page. Note that the URL of the page in the browser address bar is different to the one you clicked on. In the example given here the original URL was:

http://bnb.data.bl.uk/id/resource/010712074

while the address in the browser bar is:

http://bnb.data.bl.uk/doc/resource/010712074

You will be able to take advantage of the equivalence of these two URLs later in this exercise.

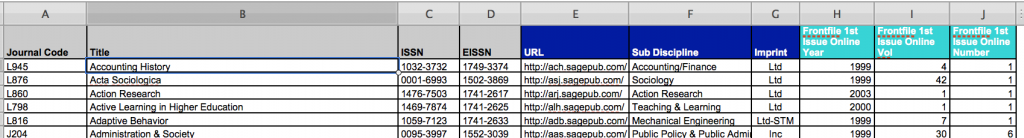

While the HTML display works well for humans, it is not always easy to automatically extract data from HTML. In this case the same information is available in a number of different formats, listed at the top righthand side of the display. The options are:

The default view in a browser is the ‘html’ version. Offering access to the data in a variety of formats gives choice to anyone working in the API. Both ‘json’ and ‘xml’ are widely used by developers, with ‘json’ often being praised for its simplicity. However, the choice of format can depend on experience, the required outcome, and external constrictions such as the programming language or tool being used.

Google Spreadsheet has some built in functions for reading XML, so for this exercise the XML format is the easiest one to use.

XML for BNB items

To see what the XML version of the data looks like, click on the ‘xml’ link at the top right. Note the URL looks like:

http://bnb.data.bl.uk/doc/resource/010712074.xml

This is the same as the URL we saw for the HTML version above, but with the addition of ‘.xml’

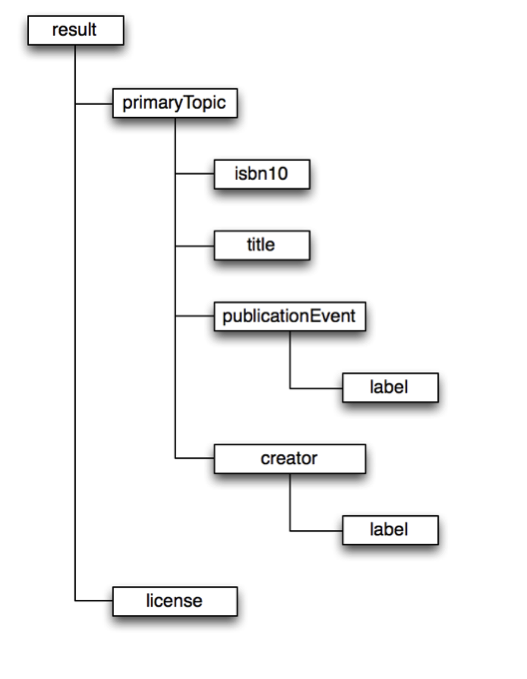

XML is a way of structuring data in a hierarchical way – one way of thinking about it is as a series of folders, each of which can contain further folders. In XML terminology, these are ‘elements’ and each element can contain a value, or further elements (not both). If you look at an XML file, the elements are denoted by tags – that is the element name in angle brackets – just as in HTML. Every XML document must have a single root element that contains the rest of the XML.

Going Further

To learn more about XML, how it is structured and how it can be used see this tutorial from IBM: http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/xml/tutorials/xmlintro/

- Can you guess another URL which would also get you the XML version of the BNB record?

- Look at the URL in the spreadsheet and compare it to the URL you actually arrive at if you follow the link.

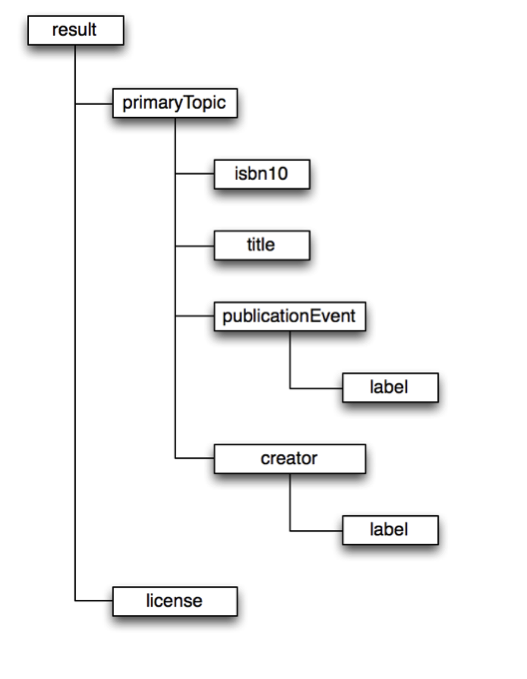

The structure of the XML returned by the BNB API has a element as the root element. The diagram below partially illustrates the structure of the XML.

To extract data from the XML we have to ‘parse’ it – that is, tell a computer how to extract data from this structure. One way of doing this is using ‘XPath’. XPath is a way of writing down a route to data in an XML document.

The simplest type of XPath expression is to list all the elements that are in the ‘path’ to the data you want to extract using a ‘/’ to separate the list of elements. This is similar to how ‘paths’ to documents are listed in a file system.

In the document structure above, the XPath to the title is:

/result/primaryTopic/title

You can use a shorthand of ‘//’ at the start of an XPath expression to mean ‘any path’ and so in this case you could simply write ‘//title’ without needing to express all the container elements.

Going Further

- What would the XPath be for the ISBN-10 in this example?

- Why might you sometimes not want to use the shorthand ‘//’ for ‘any path’ instead of writing the path out in full? Can you think of any possible undesired side effects?

Find out more about XPath in this tutorial: http://zvon.org/comp/r/tut-XPath_1.html

Using the API

Now you know how to get structured data for a BNB item, and the structure of the XML used, you can extend the Google Spreadsheet you created in Exercise 1 to display more detailed data for the item.

Google Spreadsheets has a function called ‘importXML’ which can be used to import XML, and then use XPath to extract the relevant data. In order to use this you need to know the location of the XML to import, and the XPath expression you want to use.

In Exercise 1 you should have finished with a list of URLs in column C. These URLs can be used to get an HTML version of the record. To get an XML version of the same item, you simply need to add ‘.xml’ to the end of the URL.

The XPath expression you can use is ‘//isbn10’. This will find all the isbn10 elements in the XML.

With these two bits of information you are ready to use the ‘importXML’ function. In to Cell D6, type the formula:

=importXml(concatenate(C6,".xml"),"//isbn10")

This creates the correct URL with the ‘concatenate’ function, retrieves the XML document, and uses the Xpath ‘//isbn10’ to get the content of the element – this 10 digit ISBN. N.B. Depending on the locale settings in Google Docs, it is sometimes necessary to use semicolons in place of the commas in the formula above.

Congratulations! You have used the BNB API to retrieve XML and extract and display information from it.

You have:

- Understood the URLs you can use to retrieve a full record from the BNB

- Understood the XML used to represent the BNB record

- Written a basic XPath expression to extract information from the BNB record

Going Further

- How would you amend the formula to display the publication information?

- Now you have an ISBN for a BNB item, can you think of other online resources you could link to or use to further enhance the display?

- How would you go about bringing in an additional source of data?

To see one example of how this spreadsheet could be developed further see https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0ArKBuBr9wWc3dEE1OXVHX2U2YTkyaHJxWjI2WTFWLUE&usp=sharing

- What new source has been added to the spreadsheet?

- What functions have been used to retrieve and display the new data?

- Why is the formula used more complex than the examples in the two exercises above?